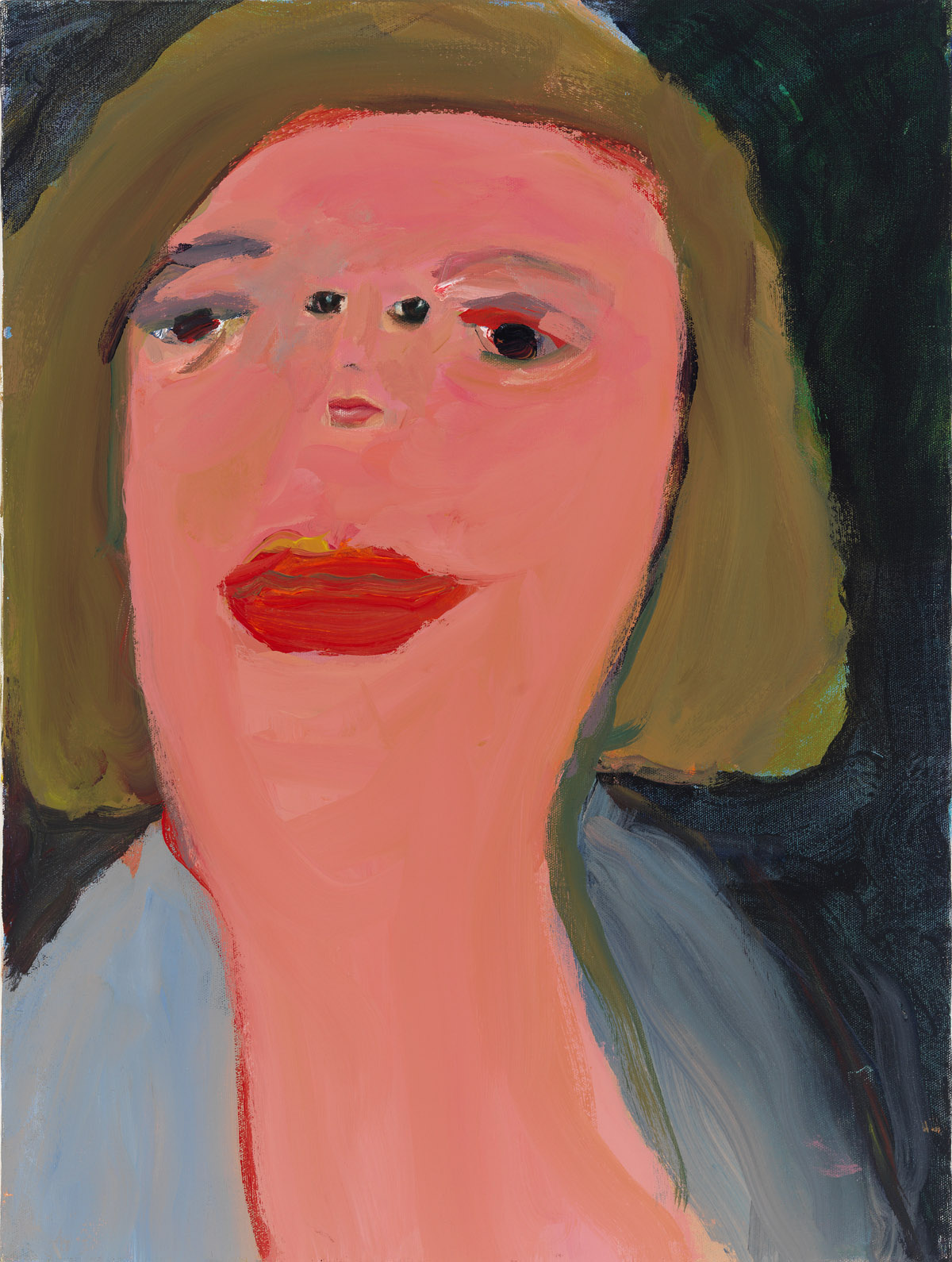

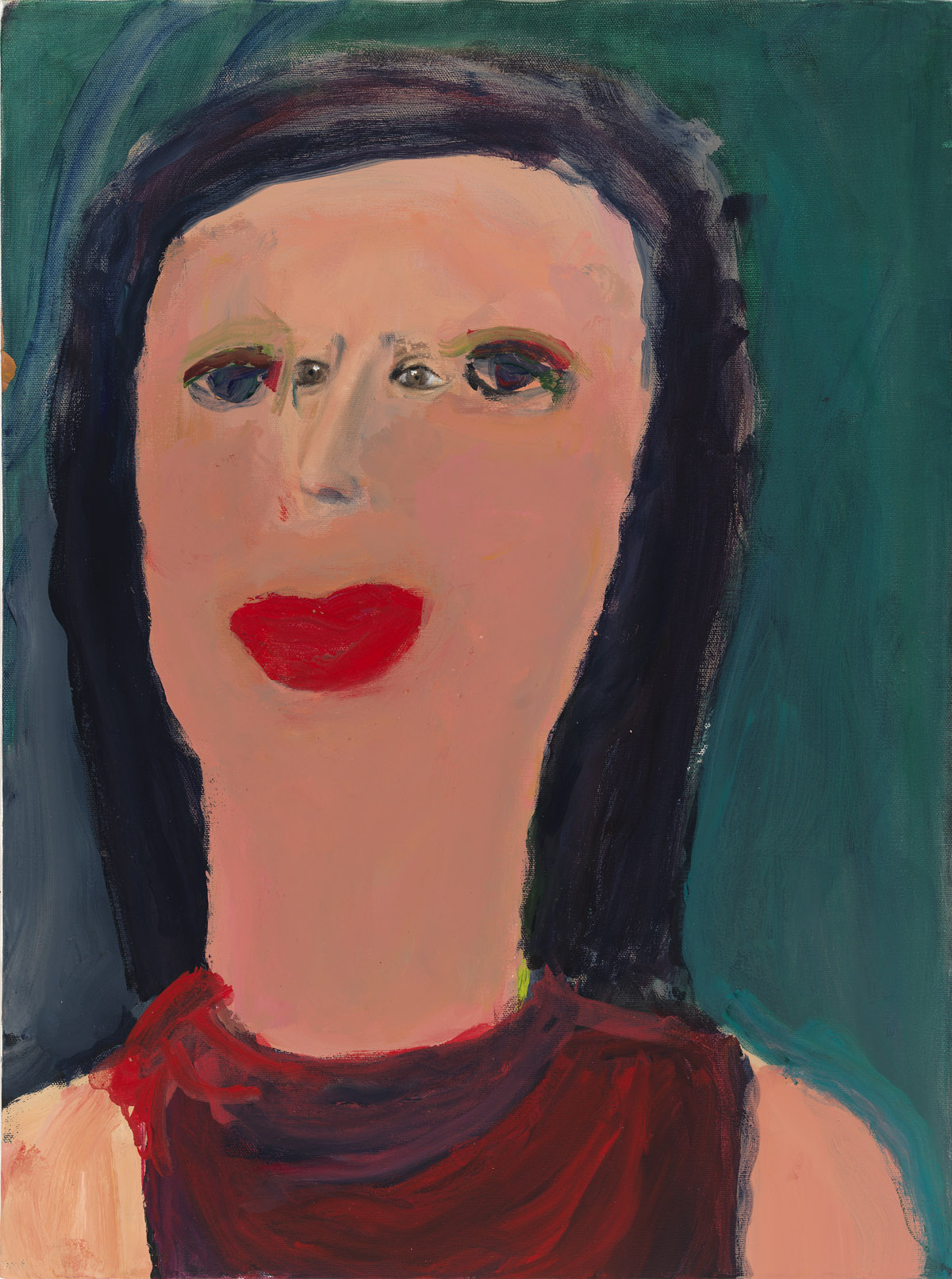

My interview with Kyle Staver is finally up on Figure/Ground. It was an honor to talk to her!

(Interviewed June 20, 2016, in Brooklyn, New York)

Kyle Staver: I was born in April in northern Minnesota and when I was sixteen I went to a boarding school outside of Chicago called Ferry Hall [now Lake Forest Academy].

Gwendolyn Zabicki: I went to Lake Forest Academy! It was magical.

KS: I wanted to get out of Minnesota and my best friend went to the academy. I grew up with him and he said, “you should go to Ferry Hall,” so I told my parents I wanted to go to boarding school. It was wonderful. I got a very different kind of education than I would have got in northern Minnesota. I had teachers that were extraordinary women and that wasn’t really true where I was before. They had a sense that you could achieve anything you wanted and I didn’t know that. So I’m really grateful for that. It was near Chicago and Chicago is a big city. The biggest city I grew up with was Deluth, so there wasn’t that sense of things happening. Then I went to a college in Missouri, because my parents said no to art school. They had no idea what it was, but I didn’t either. I went there for one year and then went to the Minneapolis College of Art and Design as a sculptor. After that I went to the Camberwell College of Art in London and then I was a sculptor for years. I moved to New Haven and made my first painting when I was 29 years old. When I make paintings I make them like a sculptor. I feel like I build them. I don’t feel like John Singer Sargent, I feel like a coal miner.

GZ: Was London part of a study abroad program?

KS: I fell madly in love with a British sculptor and ran off with him. I went to school at Camberwell while I was there. My parents completely had a fit. So I went there, came back, made my first painting, and then I was a baker. It’s fine and well to be an artist, but you need a way of making money, so I made money as a pastry chef and a bread baker. When I was in New Haven, I was in charge of the baking department and I only hired painters. They were mostly Yale painters and it was extraordinary. They taught me to paint. And then I thought, “I’ve got to go to Yale.” So I applied, got wait-listed, painted my brains out for a year, and then I got in at 31.

GZ: Who were your teachers at Yale?

KS: William Bailey, Lester Johnson, Mel Bochner. Probably the person who changed my life the most was Andrew Forge. I was there in the 80’s. John Currin and Lisa Yuskavage were the year ahead of me. There were a lot of painters there-- it was truly a painting school and it was intense. I stayed one year after I graduated. I was still baking, and then I came to Brooklyn. I came here in 1988. Then I just painted.

GZ: Chicago has these great art schools, but for the last five, six, seven years, I go to the MFA painting shows and there’s no painting in them. There are painters in the painting programs doing installation work or performance or making videos. Painting dried up to a trickle and then in the last year it all came back.

KS: That’s what happens though, you know? I went into a shop the other day and they had elephant bell bottoms. They’re horrible. I remember when I was in northern Minnesota, drinking in the woods. You’d have to pee and so you’d go in the woods and you’d always pee on your elephant bell bottoms. It was horrible. It made no sense, but they’re back again. Things are cyclical.

GZ: I think now painters in MFA programs are looking to you. They are looking at your work, and they’re looking at Nicole Eisenman, Dana Schutz, Katherine Bradford-- all incredible painters who happen to be women. They want to do big, beautiful, figurative, exciting painting with movement and color.

KS: I think there is a huge need to communicate, to tell stories. It is primal. I’m not saying that installation pieces aren’t communicating, but there is such a long history of telling stories with paint. One can feel like a Neanderthal man discovering fire. We are making this transformation on canvas. We can also re-address the old stories from our current perspective, and add new interpretations.

It is similar to reading books again and again. I have read Anna Karenina over and over. In my 20s, I thought she should’ve just left the guy. As I’ve read it in each decade of my life, it becomes a deeper and more confusing read. I realized there was no solution; she really was trapped.

Titian’s painting, “The Flaying of Marsyas” (c. 1575), was absolutely political. But, if someone were to paint that subject now, it would have a different meaning. I think of Angela Dufrense’s copy of the Courbet painting, “Woman with White Stockings” (1864), at the Barnes Foundation. Angela comes from a very different point of view, from a very different time. She turns it into something else, something more powerful for now, for this audience. Her version is so wonderfully raunchy.

If I paint the myth of Leda and the Swan, I can shift the story. In my version, it is consensual. It becomes about two teenagers in love. I can change the ending for her; I can protect her. I think that is really exciting, and I can still hat-tip to the greatest painters who ever lived.

I am much more interested in Titian or Courbet being present in my studio, than my peers. I look at my peers, but as Matisse said, “Stay away from the painters of your generation.” Picasso, on the other hand, went to every possible exhibition. He was so interested in his contemporaries and what they were doing. Matisse just didn’t want to let them in. I love all kinds of painters who are painting now, and yes, there is something in the air, which is available to all of us. But, I don’t take my contemporaries into the studio. I want to go to the source.

GZ: Is that part of your own teaching, or how you were taught as a painter?

KS: I ask students all the time, “Who is your favorite artist?” and they will mention a contemporary painter. I tell them to go to the source-– to look at who that artist is looking at. Teaching is tricky, though. I think of an experience I had with a recent painting. It includes the image of a dragon. I didn’t know how to paint a dragon. What if I’d taken a dragon class? Instead, I just sweated nickels over that dragon until it communicated dragon-ness to me and hopefully to you. It’s kind of how pornography works.

GZ: Pornography? How so?

KS: With pornography, there is an airbrushed picture of naked boys or girls. It’s put in front of you, and it makes you go into your own head, and page mentally through the things you think are erotic. In other words, it is just a trigger to stimulate you to think of your own images, to go through your own files. But, that is not how Rembrandt functions. He was not trying to remind you of something. He was trying to change the world for you.

I love Renoir, and the late work of Renoir is so sexy. They are the naughtiest paintings in the world. Some people don’t like his “cotton candy” fat women, but those were his women. Real sex is ugly and messy, and that is how I feel about Renoir’s paintings. You can feel him in there. He doesn’t care if you’re uncomfortable because he’s painting. The connections he has to his paintings are so intimate. He was an old man when he made that work in the 1890s and 1900s, and he wasn’t going to like the same things a 20-year-old thinks is sexy. He said, “When I’ve painted a woman’s bottom so that I want to touch it, then [the painting] is finished.” What is a better wish, really, than for a painter to find a way to fuck his paintings?

GZ: That’s kind of like re-reading Anna Karenina again and again. Sex changes as you mature. Have your interests changed over time, in terms of other art?

KS: When I saw the recent Degas monoprints exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, I couldn’t believe how much pleasure and information was in them. When I was younger, I had a shorter attention span and I couldn’t make that connection. I’ve been painting long enough that the excitement of looking at something is really fierce now. That might be the consolation prize for getting older. I have gotten much more open.

GZ: In your work, you use the whole arena of the canvas. The movement in the paintings is so active. It goes all the way up through the edges. Can you talk about that?

KS: In some early Italian Renaissance painting, like Piero della Francesca, it is like the painting is happening purely on intellectual level. It happens in the mind, from the neck up. It is like church; it’s always contemplative. You see the moment before or after something has happened -- not the act. But with someone like Rubens, he paints the moment. You are in the action. Even if Rubens is painting something horrible, there is so much joy in it. He doesn’t have the capacity to be without joy.

GZ: Yes, I just saw the Rubens painting, “The Banquet of Tereus” (1636-38), at the Prado. There is a severed head in that painting, but it is still joyful.

KS: In the Rubens painting, “Rubens, His Wife Helena Fourment, and Their Son Frans,” (c. 1635), at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he shows his second wife, who had been his mistress. He was about 56, and she was 16 and also his niece. It’s not permissible in our culture today, but I believe he loved her. Do you know the best part about that painting? In the painting, he has taken off one glove, so he can pinch the little fatty mound at the base of her thumb. It is so perfect. It’s so hot. There is a macaw in the background and a statue with protruding breasts. It is a wild, passionate love letter to a girl who he adored.

GZ: Are you joyful when you work?

KS: I have to be neutral when I work. I have a fairly rigid schedule. I paint every day. I have to keep the drama from my life out of my studio. I have wonderful friends and great support. I don’t do crazy things anymore. I did when I was young. Now that I am older, I need to just paint.

GZ: What is your daily routine?

KS: I wake up at 5 AM, feed my cats, and have coffee. I work on my Facebook project, where I post albums of three related paintings, from three different artists. So, I album hunt for about an hour in the morning, and then I go to the gym. I come back and start painting at about 9:30. I paint until 2:30. Then I read,and go back in the studio and mess around.

GZ: That sounds like a dream.

KS: It is a dream.

GZ: And your studio is in your home. Do you ever go up there at midnight get something out that just came to you?

KS: I don’t like painting at night. I don’t like how I feel in the studio at night.

GZ: Do you only use natural light? The light in your painting is so special. Everyone is back-lit. Does it relate to other painting, like Rembrandt?

KS: The light in Rembrandt painting kills me. Goya kills me. As for my studio, I only have crappy light. I always thought it was fine, but, over the years, friends and family told me it was awful. I have a big skylight, but it is facing the wrong direction. It was in the house when I got here. I’ve been here for 22 years, in the same studio. It’s small, but it is mine. I don’t ever want to leave. I don’t have many people come to my studio. I can be mercurial, so this way, I can come out of my studio Attila the Hun or Sarah Bernhardt.

GZ: Can you tell me about a piece of advice or a recent breakthrough that just blew your socks off?

KS: I was working on an annunciation painting. I had painted the angel and putti, and there was something wrong with it. I was thinking, “Maybe I just can’t paint. Or, maybe the Bible just isn’t humane enough.” I was working on the angel, and I did something to it that made me laugh out loud. I thought, “Well, if it’s not funny, it is bad.” It made me think of the Rembrandt drawing of a naked woman rolling down her sock. There’s a red indentation on her leg from the sock. There’s no woman in the world that can’t relate to that. I am instantly connected, because it is something I have lived. It is such an observed thing, so seen and perfect. That makes it funny.

GZ: Yes, it is a piece of humanity, an insight into a character.

KS: That is really important to me. Animals can also function as signifiers that way. Animals act like a chorus. If you don’t know what is going on in a painting, just look at the animals. The animals will cue you into how you are supposed to be responding. Sometimes the animals in my paintings are the only things that are making eye contact with the viewer.

Recently I was watching a video clip of a dressage horse, and I realized it was a good analogy for painting. The rider was completely attached to the horse; there was no separation between him and the horse. The rider was in complete control, with no hint of struggle. It was the most incredible thing, and I thought, “That is what I want from painting.”

I used to be a one-session painter. I was a cowgirl painter. If I didn’t get the painting done in one session, I would start again. There might be a tiny corner of the painting that worked, but I couldn’t do anything with it. If I touched it, it was like it died. It was so fragile. I don’t feel paintings are fragile anymore.

Mel Bochner said to me once, “There is no such thing as an overworked painting. It’s just not done.” When I was making those fast and furious paintings, he asked me, “Who’s in charge here – you, or the painting?” I felt like I wasn’t in charge. Now, I take advantage of the elements and passages that surprise me, but I am in charge.

When I was young, I wanted the whole act of painting to be a rodeo. You open the gate and here I come! My horse would go wild, and I would try and hang on. The primary, underlying force was fear. Somehow I believed that being in control was wrong.

Now, being in control, and feeling my painting in every possible way, is what I want. I want more and more from my painting as I get older. In the dressage video, the only part of the horse that wasn’t completely under control was its tail, which was swishing. It was just joy, delight, and connection. That is what I want in painting.