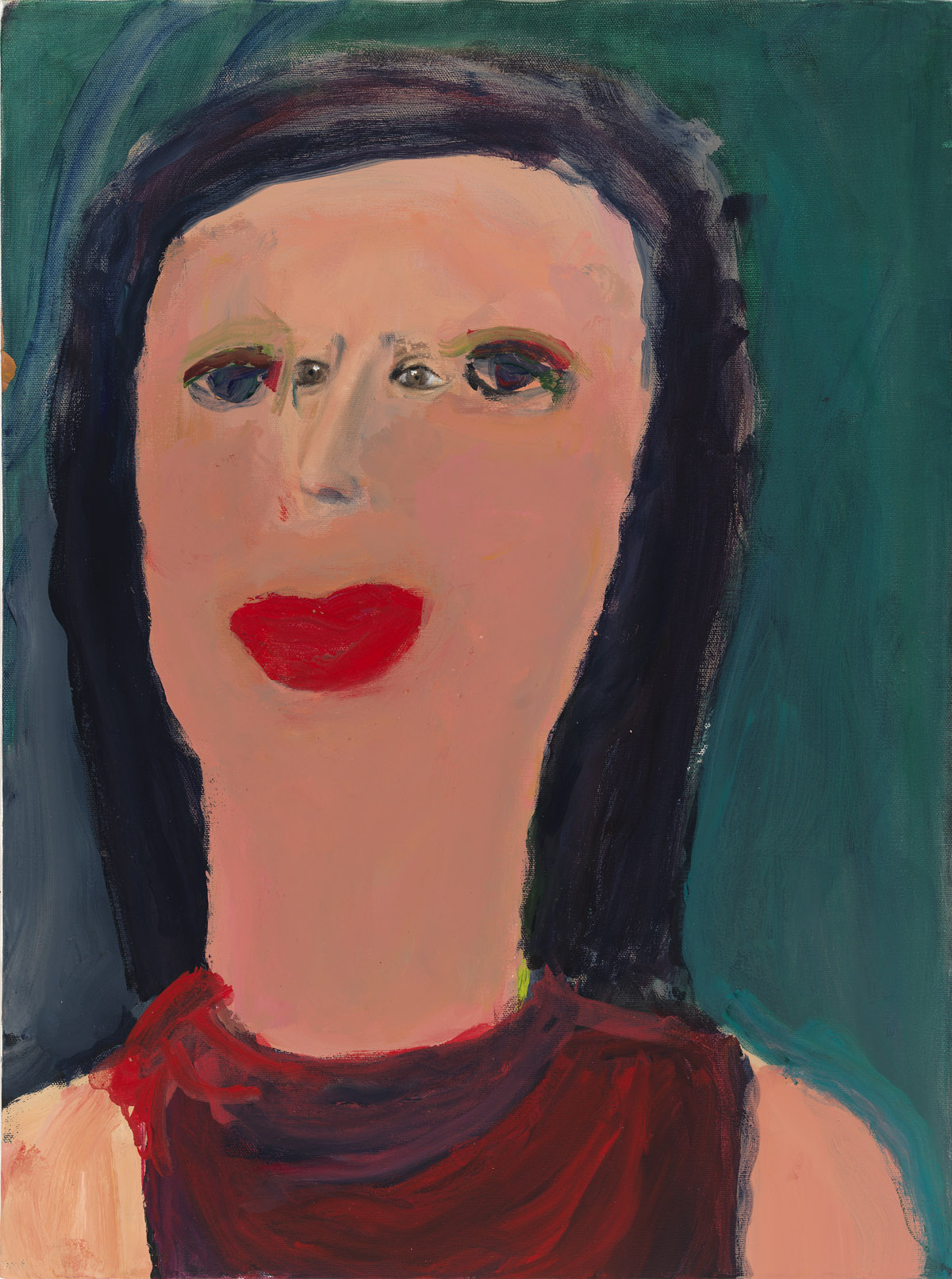

Margot Bergman, “Grace Jane” (2012), acrylic on found canvas, 24 x 18 inches (all images courtesy Anton Kern Gallery, New York)

Margot Bergman paints boldly simplified portraits of women on top of found paintings, which she salvages from flea markets. The found paintings typically contain a portrait done in a conventionally realist style. By the time Bergman has finished, she has made a larger portrait of a woman that almost completely absorbs the smaller, earlier faces, leaving only the eyes and occasionally nose and mouth peering through the layers of paint. Think of the process as digestive, one painting methodically devouring another. The premise is simple, but the results are not.

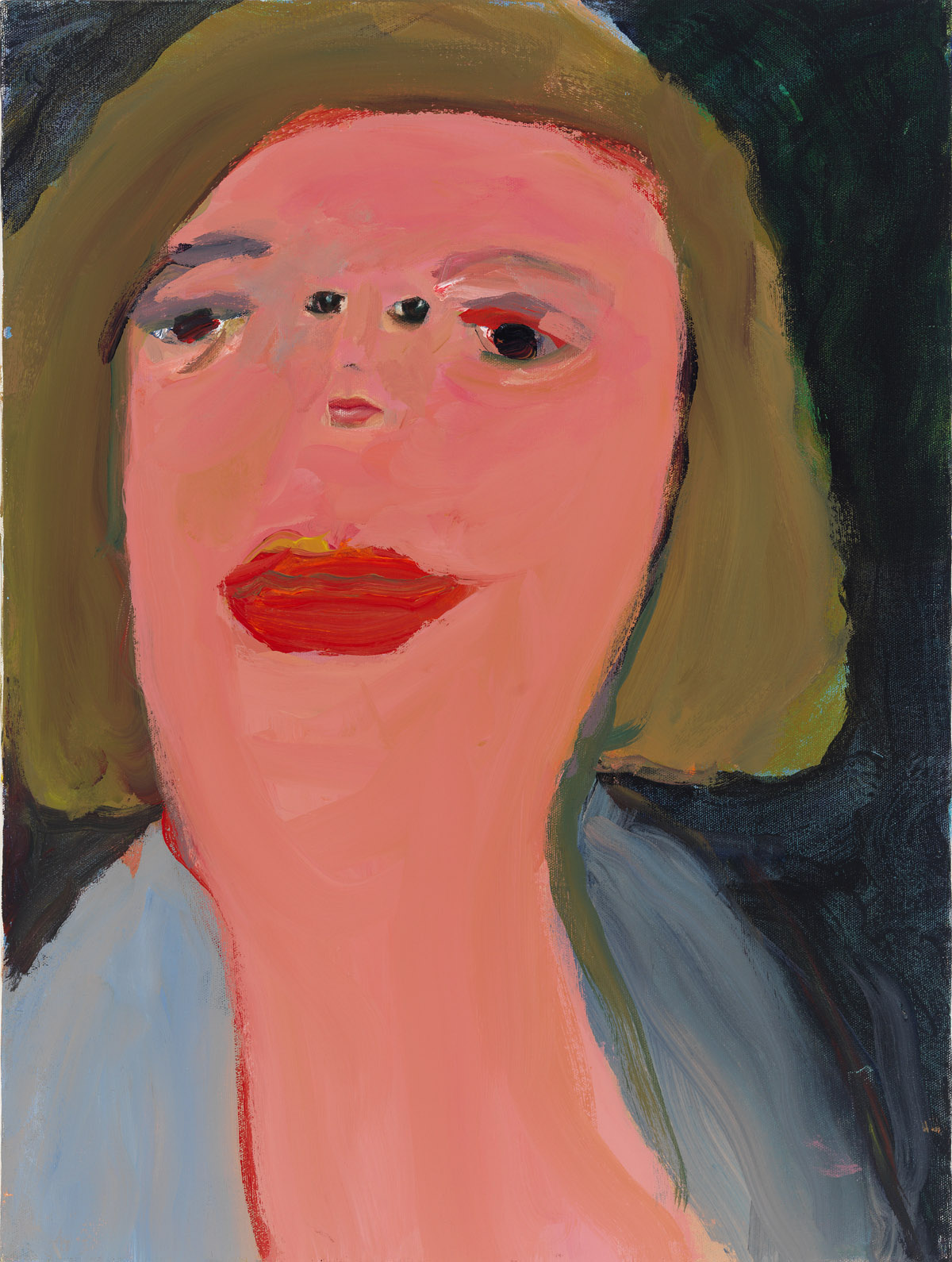

Bergman’s style has been called neo-expressionist, child-like, and primitive. You get the idea; she takes a direct approach to applying the paint, and often uses a loaded brush to make flattened, simplified faces. However, look again at the areas of blue peering through the layers of pink, and the way the colors hint at modeling and volume. In a painting like “Auntie Gladyce” (2012), Bergman employs a variety of oranges (for hair) to frame a face, which is rendered in different shades of pink and red (the large scarlet lips are especially striking), while the blouse and background are rendered in a range of greens. Clearly, she is neither primitive nor child-like when it comes to color.

Margot Bergman, “Auntie Gladyce” (2012), acrylic on found canvas, 23 3/4 x 17 3/4 inches (click to enlarge)

The juxtaposition of the found painting’s conventional realism with Bergman’s broadly applied additions calls into question the critical division between realist and primitivist art. Is the earlier painting – which we see evidence of in Bergman’s work – more sophisticated and deft than what the artist does? By dissolving the border between these styles, Bergman gently nudges us to reconsider portraiture. Is it about surface appearance, or brand name recognition, or something else less nameable? While Bergman’s paintings are apt to initially strike viewers as benign and friendly, there is something strange and disturbing about seeing four eyes lined up, like ships on the horizon, as they are in “Auntie Gladyce.” Which face are we supposed to look at, because it is hard to look at them simultaneously? “Auntie Gladyce” is the relative that scared you as a child, or that you tolerate during the holidays. She is the black sheep of the family.

Once you acknowledge there is something off about these determinedly cheerful faces and their big red lips, then you might begin to see them differently. It seems as if Auntie Gladyce has put on too much lipstick. Why are her eyes – three of the four – rimmed in red? Is that a real smile I see, or just a façade? Bergman’s women are outlandish, haggard, theatrical, overbearing and annoying. Do we really want a portrait of someone staring at us like that, with two sets of eyes? Well, actually we do, because there is also something sympathetic, tender, and gentle about these wonderful paintings. Although it is not immediately apparent, these are portraits of stalwart women who have been deeply damaged and perhaps even broken by the world, and yet they persist. Their resiliency is heroic, a testament to their grit.

Margot Bergman, “Jo” (2015), acrylic on canvas, 34 x 28 inches

Amazingly – and perhaps not so surprising – the artist, who is in her early 80s, is having her first New York exhibition, Margot Bergman at Anton Kern (June 30 – August 19, 2016). A long-time resident of Chicago, where she has exhibited her work, Bergman’s paintings possess a psychological depth that is rare in contemporary portraiture, which emphasizes surface appearance over almost all else. Bergan’s portraits are about containing multitudes. The four eyes – the smaller face both emerging and partially submerged in the larger portrait – becomes a site for all kinds of speculation; they literally and metaphorically open our eyes to all kinds of unlikely possibilities.

One of the found faces weirdly reminded me of George Washington, as if the original artist were channeling Gilbert Stuart’s unfinished portrait of George Washington, also known as “The Athanaeum” (1796). But Bergman doesn’t always work on found canvases, as with the sparely linear “Jo” (2015), which challenges our notions of finished and unfinished. Bergman’s preoccupation with eyes calls to mind the fascinating modernist painter John D. Graham (1886-1961), whose portraits of cross-eyed women constitute a body of work that has yet to be fully reckoned with, even though he was an important and influential friend to Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning, among others. It is wrong to think of Graham’s portraits as the bizarre curiosities of a lesser painter (as one writer has mistakenly characterized him), unless you really believe in hierarchical thinking and status tracking. Let’s not make a similar mistake with Bergman, whose portraits are deserving of more attention.

I don’t think of Bergman’s portraits as eccentric; rather, they are necessary reminders of the perils of being alive. They remind us that we are made up of more than one being, that we all hear voices – be they our parents, or our friends, or people we want to smother, not necessarily with love. Bergman uses a synthetic visual language that is all her own. Her unpolished style is not another manifestation of parody, but a means of trying to get at something we all experience yet inevitably seek a way to avoid or forget: the nameless, unrelenting pain that accompanies a consciousness with any degree of sensitivity. You know, the kind that jolts you awake in the middle of the night before sleep mercifully returns to overtake you.

Margot Bergman, “Audrey Ray” (2012), acrylic on found canvas, 23 3/4 x 18 inches

By painting on salvaged works and making portraits that come across as unfinished and raw, Bergman reminds us that the surface is the least interesting aspect of a portrait, that recognizing someone, or someone’s stylishness, is really about what magazines you subscribe to, and what mass media you attach yourself to, like an octopus. There is nothing smooth or slick about Bergman’s portraits. They don’t go down like honey. They are enigmatic and distressing, mysterious and funny. More importantly, they are disturbing and true.

Margot Bergman continues at Anton Kern (532 West 20th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through August 19.