http://figureground.org/a-conversation-with-matthew-metzger/

Matthew Metzger lives and works in Chicago where he is Assistant Professor in Studio Arts at The University of Illinois at Chicago. Matthew was awarded his BFA from The University of North Texas and his MFA from the University of Chicago. Since graduating in 2009, he has exhibited at The Smart Museum of Art in Chicago, The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Sikkema & Jenkins Co. in New York, Arratia Beer in Berlin, and Regards in Chicago, more recently, at Expo Chicago. He is also co-editor of the publication SHIFTER. http://matthew-metzger.com/home.html

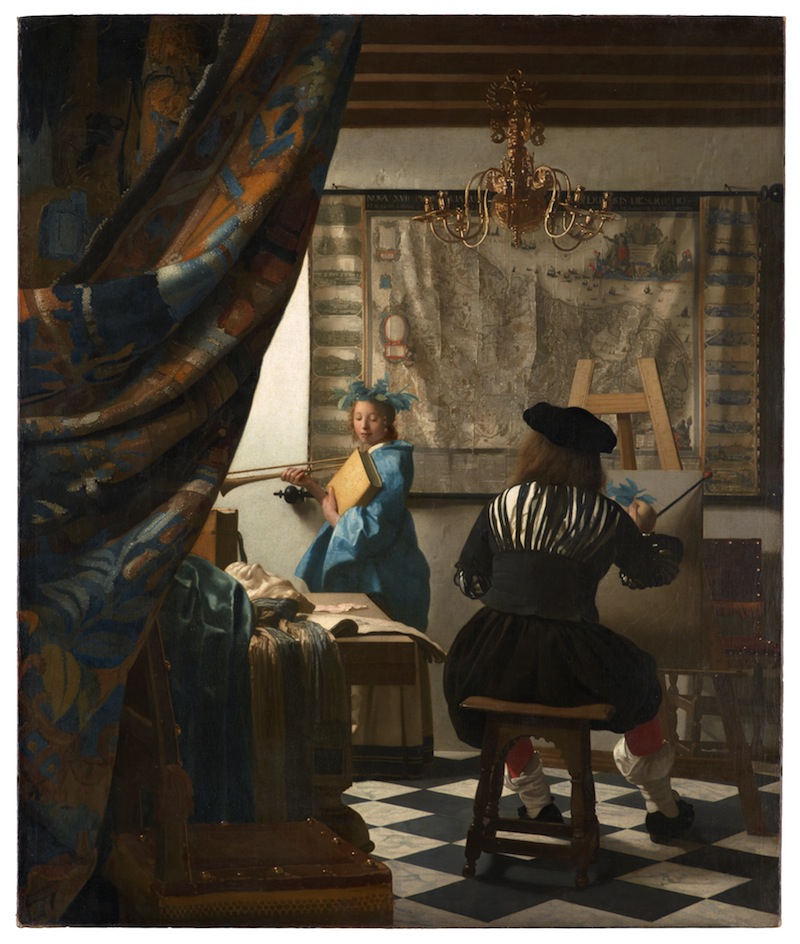

Your hyper-detailed painting of a machete, The Condition, was the standout work for me this year atExpo Chicago. Why did you think it necessary to rework this painting?

Paintings are never finished. Sometimes I accept that and move on. Other times, the painting is rather demanding in its need for labor, and in turn, labor’s need to be amplified as a concept for the work. One question that has been generating this series of machete paintings is about whether one can express oneself at the very same time one is laboring over something. At each moment this painting has been exhibited, afterwards I want it to do more, so then I begin to do more.

© Matthew Metzger, The Condition. Medium: Acrylic and Oil on Honeycomb Fiberglass Panel, Size: 24 3/4″ x 24 ¾”

Date: 2015, Courtesy of Arratia Beer, Berlin and Regards, Chicago.

Date: 2015, Courtesy of Arratia Beer, Berlin and Regards, Chicago.

The knife in the painting runs from one edge all the way to the other and it splits the painting into two halves. The knife represents separation, orientation, and is undeniably connected to political violence as well?

The project stemmed from a Michael Fried essay in 1965 called Three American Painters. In the essay he is writing about post-painterly Abstraction. At one point he remarks that Morris Louis’ work comes from the wrist. It sparked these ideas about how one thinks about the body and its relationship to expression, and perhaps the location on the body where expression originated. If Morris Louis’ work comes from the wrist, then perhaps Jackson Pollack’s comes from the shoulder. I began to ruminate on what is that relationship was about, going from the shoulder to the wrist, and what’s the function of the shoulder now? At points of intense labor where the shoulder is being used can one also express oneself simultaneously? Or is there a paradox between working and expressing? Do they ever find their way together? And if they did find their way together where might it be found in the body today? So it became a location for thinking through a simultaneity of labor and/with expression. Quickly in this rumination, expression for me lingered in ‘the political’ and labor was found in the echoing of a thing absent the hand, labor. Either way, where they meld and what sort of tool houses both sides of this binary, of this division line, is of a particular interest to me. The machete is the one blade that is deeply rooted in the shoulder, a personal, domestic, and political tool that always and already severs and joins.

© Matthew Metzger, The Condition (detail – right side). Medium: Acrylic and Oil on Honeycomb Fiberglass Panel, Size: 24 3/4″ x 24 ¾”

Date: 2015, Courtesy of Arratia Beer, Berlin and Regards, Chicago.

Date: 2015, Courtesy of Arratia Beer, Berlin and Regards, Chicago.

You can appreciate a good painting in a superficial way, but there are always several deeper layers beneath it. You can admire the technical ability that it took to make this and maybe a fancy chef like Paul Kahan would see it and connect with the subject and buy it. But the knife, it’s a red wheelbarrow; it contains everything.

These paintings have been an ongoing meditation. When I’m painting them [the blades] and I’m standing here this perspective is right, but when I come over here and I’m painting this [the handle] this perspective is all wrong. The condition is dependent on where you are in relation to the thing. The perspective is always distorted to some degree. The paintings are inherently always distorted and abstracted because the body can move and the painting can’t.

When you make work that is so real, it starts to fall apart in front of you. It becomes abstract again.

That happens all the time when you think about how far to push things. I am tied to the belief that paint can be alchemic in a way. I think the illusion that paint has the capability of reconfiguring itself through becoming something other than itself has always been fundamental to painting. We often think a painting is either figurative or abstract and on a circle, figuration is at one end and abstraction is on the opposite end, and the painter/painting is always somewhere on the circle in proximity to both, but at the end, I realize it’s not a circle at all, it’s actually a corkscrew. I know it sounds ridiculous or perhaps a little too dogmatic, but in painting today there is just not enough insistence on forcing paint to do what the artist wants it to do. It’s a material like anything else in the world and you can make it do whatever you believe it can do.

© Matthew Metzger That Which Can’t Be Played (Composition #7) Medium: Acrylic and Oil on MRMDF Panel,

Size: 11 ⅞” x 11 ⅞” Date: 2015, Courtesy of Arratia Beer, Berlin and Regards, Chicago

Size: 11 ⅞” x 11 ⅞” Date: 2015, Courtesy of Arratia Beer, Berlin and Regards, Chicago

It’s a fear-based thing. A lot of artists are afraid to fail. I’ll never be as good of a painter as Caravaggio, so why try? It’s also a huge commitment of time. It takes years to learn to paint well and in the meantime your friends and family are watching you make this awful work and somehow not judging you for it. You have to not feel embarrassed by your own past (bad) work and to accept that it takes years to figure this stuff out. It’s a good thing actually, because you will have this pursuit that will sustain you throughout your entire lifetime. Older painters have told me that even after everything else ends, marriages, jobs, relationships, they always have painting and that it is endlessly interesting and that there are new things to learn and do.

Your work made me think of Mark Rothko’s paintings. He was looking for some sort of universal truth that would exist in any time and anyplace. Rothko had a pretty traumatic life and even though he wanted to make paintings that transcended politics, he was still responding to the fact that WWII had made the world a terrifying place. His paintings were about expressing basic human emotions – depression, ecstasy, terror. I feel that in a way, even though you are at the opposite ends of the spectrum, the extremes of representation and abstraction, you are both after the same thing, and that your work slides back and forth between the two. He was deeply depressed and made this untitled piece shortly before he killed himself. It was painted in 1969, the year of the moon landing. I look at this and I know this is the surface of the moon. It’s abstraction sliding back into representation. There is that horizon line, just like your painting, and the same palette too. The moon was the coldest, loneliest place imaginable and we got there using military technology. This came from the same funding and research that was meant to keep Russia in check after the war. Rothko was a Jewish painter born in Russia who immigrated to the United States and he must have felt this event in an extremely personal way.

He was after something that preceded language, a thing that can’t be located until after the fact.

In Paul Virilio’s book The Accident of Art the idea that all art comes from trauma is discussed, and that even surrealism for example is a type of coping with the War. The idea is mentioned that you can’t look at stacked objects without seeing stacked bodies, post-Holocaust for instance. I am very interested in this. Especially what generates the production of work in an artist’s studio and is it really that direct as to say that trauma is a common denominator? I don’t know, but I think it has certainly stayed with me since I read it.

Going back to the horizon line idea, the horizon is the end of something. In our emails you wrote something like, The Condition [the title of the painting] is living in a state of awareness about the limits of perspective and language.

Yes, for a long time art making has had a tendency to privilege intellect over feeling. And only recently in the past few years, by breaking down my own anxieties, I’ve realized that even though we don’t have very effective language to describe our feelings, they’re always there, and usually in full force. Feeling is so much more present and dominating than a kind of idea or theory. Attempting to figure out how to cope with those feelings is a universal dilemma I think. My own curiosity is embedded in knowing that my understanding of my feelings are often embedded in theories.

Yes, that’s the thing Rothko was after.

When I’m researching ideas, they’re always embedded in the question of how you translate an untranslatable experience. In that often untranslatable experience is that which precedes language, that which is made manifest in the body. It can be a lot of feelings crowded into one. A theory is never going to be as interesting to me as the person developing it. There is a selfhood that is lacking in a lot of contemporary work—it’s vacant.

I don’t know if culturally we live in a place anymore that privileges trying to figure yourself out. Perhaps we never have. I always thought I had a very systematic, removed process of making in the studio as I attempted to explain everything and figure everything out before I actually started making work. Slowly I’m realizing that the work is becoming more embedded in questions about how to express. And maybe after I move through those questions I’ll find a language with which I can express myself. Right now it’s making images of our limitations. And from there, where do we go?

© Matthew Metzger. That Which Can’t Be Played (Composition #5), Medium: Acrylic and Oil on MRMDF Panel

Size: 11 ⅞” x 11 ⅞” Date: 2015, Courtesy of Arratia Beer, Berlin and Regards, Chicago

Size: 11 ⅞” x 11 ⅞” Date: 2015, Courtesy of Arratia Beer, Berlin and Regards, Chicago

Barthelme writes about this is an essay called Not Knowing. He wrote that artists make work without knowing how it will end up or even why they are making it. They have a style that comes from limitations and setting up some sort of parameters– in your case it is the gray primer background you always use, the length of the knife dictating the height and width of the canvas. But then after you’ve finished the work, you realize why you did it. You figure it out later, but it was in there all the time and you didn’t know it as you were doing it. You have to work that way if you want to uncover, as Barthelme put it, “the as-yet-unspeakable, the as-yet unspoken.”

Not knowing is also about privileging vulnerability, about being okay with not quite understanding. We have a tendency to jump to terms like failure, but maybe it’s not as binary as success or failure, knowing or not knowing, but rather just accepting an unavoidable incorrectness / inaccuracy while doing, and the vulnerability that results. It means that if you fail, you are failing in the aesthetic of being vulnerable versus confident vulnerability.

It takes a lot of maturity and patience to get to that point. I think that’s a good place to be and a good place for us to stop.

—

© Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matthew Metzger, Gwendolyn Zabicki (http://gwendolynzabicki.com/contact.html) and Figure/Ground with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Suggested citation:

Zabicki, G. (2015). “Conversation with Matthew Metzger,” Figure/Ground. December 21st.

< http://figureground.org/a-conversation-with-matthew-metzger/ >

< http://figureground.org/a-conversation-with-matthew-metzger/ >

Questions? Contact Laureano Ralón at ralonlaureano@gmail.com